In the Colonial period of South Carolina’s history, Fort Prince George was the king’s own bastion in the Upcountry. Built at the request of Attakullakulla and his fellow Cherokee chiefs, the construction was personally supervised by Royal Governor James Glen. Fort Prince George alone protected and maintained the immense trade from the mountains to the port city of Charleston, making the merchants and the city the richest in the Empire. The original site is now under the water of Lake Keowee.

Along the slopes of our tranquil mountains, in the rich soil of our valleys, and deep beneath the waters of our shimmering lakes lies the evidence of a time of hardship, war, and bloodshed. In the years that preceded the French and Indian War of 1754-1763, the French made diplomatic inroads with most of the Native American nations east of the Mississippi. One of the exceptions was the Cherokee Nation whose ties to Great Britain were bound by trade following the Yamassee War of 1715-1717. In return for guns, blankets, cloth, and other commodities, the British received hides, antlers, and even human scalps — all highly desired products in the markets of London. As importantly, the Cherokee had become an ally to the colony and gave the Carolinians one less enemy to fear along their frontier. As time passed, the Cherokee became increasingly dependent on supplies and trade with the British colony and increasingly anxious over the growing French presence in the Appalachians and the French influence on the rival Creeks and Choctaws. On July 4, 1753, a Cherokee delegation met with the Royal Governor, James Glen, and the

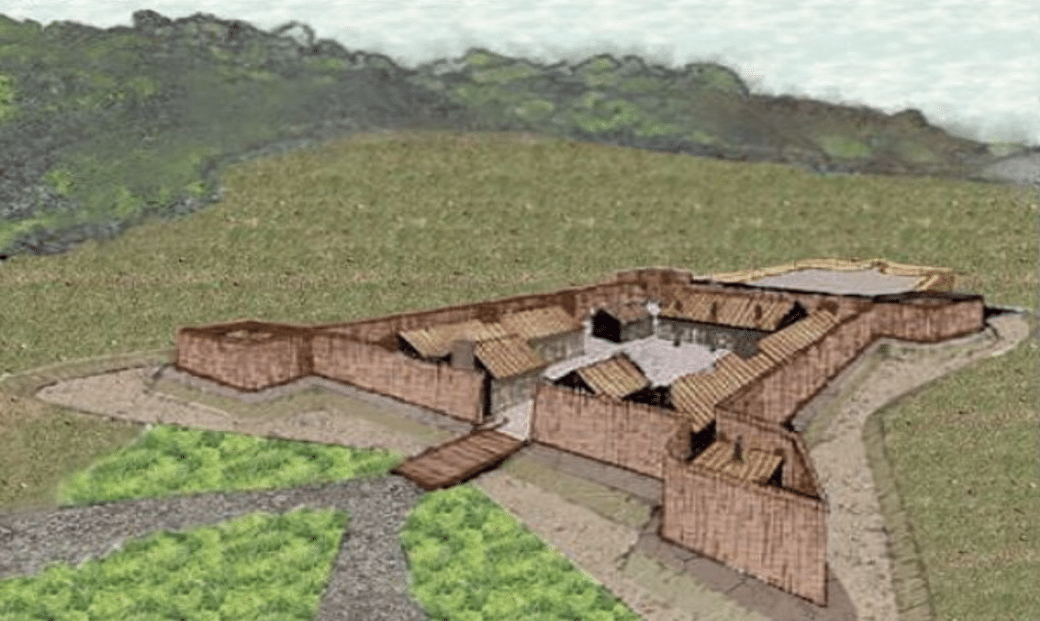

colonial House of Commons in Charleston which resulted in a treaty that allowed a fort to be constructed in Cherokee territory to protect British interests and defend the Cherokee from their enemies. The fort would be built in a great river valley the Cherokee called Keowee, the “place of the Mulberry” and named to honor George, the Prince of Wales. Prince George would become George III, king of England, in whose reign the American Revolution took place.

In return for guns, blankets, cloth, and other commodities, the British received hides, antlers, and even human scalps.

In 1756, Fort Prince George was almost completely rebuilt because of structural issues due in part to the loose, sandy soil on which it stood.

Royal Governor William Henry Lyttleton demanded that the Cherokee turn over all of the warriors responsible for the deaths of the settlers. Twenty-three settlers were killed including Catherine Calhoun, grandmother of John C. Calhoun.

The fort took only two months to complete and, with its complement of cannons and swivel guns in range of Keowee Town across the river, it was an imposing garrison. Constructed entirely from wood cut from the area, the square fort was relatively small. The walls were made of pine logs 8 to 10 inches in diameter sunk into the ground one beside the other and sharpened on top. A bastion stood at each of the four corners with a swivel cannon in each. The fort contained several wooden buildings with dirt floors which were improved over the years. The garrison was supplied with water from a well located in the center of the fort. The entire footprint of the fort, including the dry moat surrounding it, was only 200 feet square. There were, however, problems. In 1756, Fort Prince George was almost completely rebuilt because of structural issues due in part to the loose, sandy soil on which it stood. The palisades would collapse after heavy rains which would also wash dirt into the moat. Locating the fort on low ground surrounded by hills would later prove to be a costly decision by the British.

In 1758 a group of Cherokees returning home from fighting the French in Virginia became embroiled with some Virginians over horses and twenty Cherokee were reportedly killed. Taking their revenge, the Cherokee killed a group of settlers on the Yadkin River in North Carolina. The following year settlers along the Yadkin were again attacked as well as settlers in the Tugaloo and Keowee River areas. These were the acts of local chiefs and warriors who had fallen under the influence of French agents and not condoned by the Cherokee Nation. In order to preserve the now fragile alliance with the British, the Cherokee sent envoys to Charleston where they met with an angry South Carolina colonial government. Royal Governor William Henry Lyttleton demanded that the Cherokee turn over all of the warriors responsible for the deaths of the settlers. The governor needed to resolve this issue and impress the Cherokee that such attacks were not acceptable. He insisted that the situation to resolved at Keowee. On the way there, Lyttleton met with 1400 colonial troops and took the Cherokee peace envoys into custody with the intent of exchanging them for the killers of the settlers. The governor, his army, and his prisoners arrived at Fort Prince George on December 9, 1759. A week and a half later, the Cherokee turned in two of the guilty warriors in exchange for three of their chiefs. A treaty was signed acknowledging that the remaining chiefs and warriors would be held until the twenty-two Cherokee responsible for the deaths of the settlers were turned in. Signed under duress, the treaty did not hold. Chief Oconosta sided with the French and soon the Anglo-Cherokee War of 1760-1761 erupted which incurred tragedies for both sides. Early on the Cherokee attacks went virtually unchecked with massacres becoming almost

common place. None, however, was as severe as the massacre at Long Canes in present day McCormick County on February 1, 1760, where one hundred and fifty refugee settlers were attacked by one hundred Cherokee warriors. Twenty-three settlers were killed including Catherine Calhoun, grandmother of John C. Calhoun. One survivor was fifteen-year-old Rebecca Calhoun who watched from her hiding place as her grandmother and others were scalped. Five years later Rebecca would become the wife of Andrew Pickens and, eventually, grandmother to Francis Pickens, Governor of South Carolina during the War Between the States. Events went badly for the colonists early in the war. The need for soldiers to fight the French in the North meant a shortage of troops for this open warfare in South Carolina. The same South Carolinians that had built Fort Prince George had constructed a sister fort, Fort Loudoun, in the “unknown territory” farther northwest in present-day Tennessee. Both the vulnerable, low-lying Fort Prince George and Fort Loudoun were under siege in 1760 and the settlers were left to fend for themselves. The low point for the British was still to come. On February 16, 1760, only two weeks after the Long Canes massacre, Chief Oconosta asked for parlay with Fort Prince George’s commander, Lt. Richard Coytmore. When Coytmore and two of his aides proceeded to the meeting near the river, Oconosta’s warriors appeared from hiding and opened fire, mortally wounding Coytmore. The few soldiers inside the fort, fearing an escape attempt, rushed to secure their Cherokee prisoners. The first soldier through the door was stabbed to death and the next wounded. The troops opened fire killing fourteen Cherokee chiefs. Six months later, the Cherokee slaughtered the surrendered occupants of Fort Loudoun in one of the most brutal acts of the war.

In April, 1760, South Carolina petitioned General Amherst in New York for help in putting down the Cherokee uprising. He responded by sending Col. Archibald Montgomery to South Carolina to take control of the situation. Upon arrival, Montgomery raised an army and crossed the Twelve Mile River just north of Cateechee and destroyed the Cherokee town of Eastatoe. The army camped on a hill overlooking Fort Prince George at what is now Mile Creek Park. From there Montgomery launched several more incursions into Cherokee territory attacking Sugar Town and Etchoe near Franklin, North Carolina. Just outside Etchoe, however, Montgomery’s expedition came to an abrupt end. The Cherokee attacked his forces and routed them to near present day Rabun, Georgia. With this improved bargaining position, the Cherokee were willing to talk peace, but the humiliated British intended to punish the Cherokee for switching sides. The following year, in 1761, the British sent another commander, Col. James Grant to South Carolina. His mission was to settle the Cherokee issue once and for all. Grant had been with Montgomery the previous year and had learned much from the disaster at Etchoe. His army numbered 2600 men. Among the young officers were Andrew Pickens, Francis Marion, and William Moultrie whose names would become legendary. They camped at Fort Prince George for ten days, resting and waiting for their supply wagons to catch up. On June 7, 1761, Grant gave the order to cross the Keowee River and proceed deep into Cherokee territory. Three days later his army arrived at almost the exact place as the previous year’s defeat under Montgomery. This time the Cherokee were soundly routed. From there the British continued north and burned almost every major Cherokee Middle Town, returning to Fort Prince George on July 9, just over a month since their departure. On August 30, 1761, the Cherokee met with Grant at Fort Prince George and an informal peace was concluded. The official treaty was signed on December 18 by the Cherokee and Governor William Bull on his plantation near Charleston. Thus ended the Anglo-Cherokee War.

In 1762, Thomas Sumter was tasked with escorting three Cherokee chiefs to London to meet King George III. Returning the chiefs to their territory, he captured a Canadian Militia lieutenant who was in the area spreading French propaganda and took him to Fort Prince George. Thereby all four major South Carolina patriot leaders, Andrew Pickens, Francis Marion, William Moultrie, and Thomas Sumter are forever linked in history to Fort Prince George in Pickens County.

Today the original backcountry trading outpost and fort at Ninety Six is a National Historic Site. Fort Loudoun in Tennessee was reconstructed in 1980 and welcomes over two hundred thousand visitors each year. In Pickens County, our own Fort Prince George lies forgotten one hundred and fifty feet below the water of Lake Keowee.